There have been two things which have prompted me to write this today. First, I saw a teacher share some brilliant work, but which had differentiated learning objectives on it. Second, I listened to the 5th episode of the Boys Don’t Try podcast on high expectations and was reflecting on whether mine are high enough. Differentiated objectives (All, most, some or Must, should, could, or even bronze, silver, gold) are something I have absolutely used in the past, but no longer do. I might have had something like; All of you will describe the causes of the peasants revolt, Most of you will explain those causes with factual detail and Some of you will assess how important these causes were. Now I look back at this with horror. It shows a huge confusion with Bloom’s Taxonomy but it’s also about the way I wasn’t challenging all my students in the same way. I thought many schools, like us, had stopped using differentiated learning objectives but over the past few weeks on Twitter and Facebook, I have seen repeatedly that unfortunately not all schools have moved on so much in terms of attitudes to differentiation and high expectations. Differentiated learning objectives are apparently still a thing.

The Boys Don’t Try episode reminded me how important it is that we don’t limit our pupils and how we must show that all pupils could, and should aim for excellence. By having differentiated learning objectives or outcomes (which Matt Pinkett calls “an abomination” in his blog Learning Objectives: A waste of time) we are instantly saying that not all the work is achievable for all. Tom Sherrington says in his blog Rescuing Differentiation from the Checklist of Bad Practice that this sort of distortion of what differentiation is “has the effect of explicitly setting lower expectations for students at different levels within a class. Some parts of the curriculum are only for ‘some’ – not all. It’s explicit. Intentional. And this is wrong-headed. A recipe for systematic underachievement and gap-widening.” In my example above, it would seem to suggest that understanding that causes have different weights attached to them and some are more significant than others is an aspect of history that is just too much for some students. It not only places a limit on students’ capabilities, it also encourages laziness and a lack of motivation. As Matt says: “After all, why would you do the trickiest option, when you could do the tricky one and still have time to piss about.”

I would also argue this extends to tasks within a lesson. Another failure I used to make was to bolt “challenge” on to a slide or worksheet. I still see resources shared or observe lessons where this is the case. The main task will be set for all students, but for certain students there is an additional challenge. A lot of the time this challenge is never explicitly mentioned or shared, it just sits on the slide. Again the presumption is that this task is just too hard for some pupils, putting a lid on their knowledge and progress. Ross Morrison McGill says “Putting on challenge at the end of the lesson means it failed to challenge in the first place.”

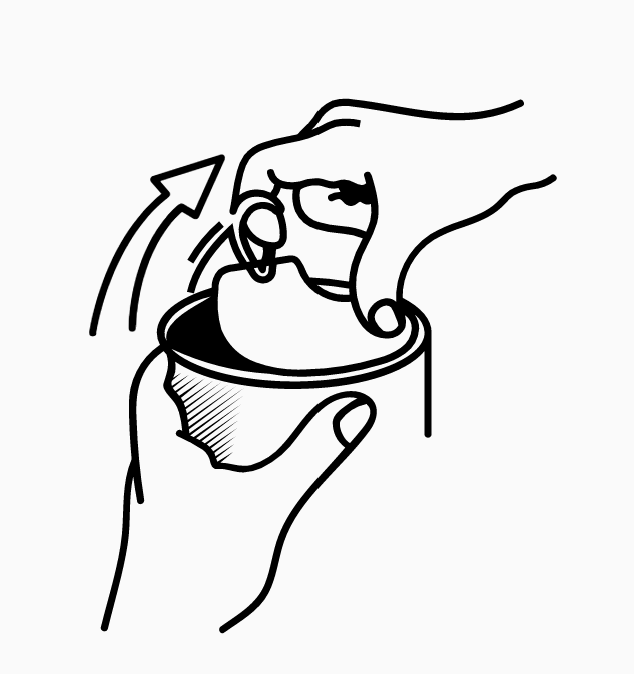

So what’s the answer? We need to stop thinking about different routes through the lesson or a scheme of work. We need to teach to the top of whatever class is in front of us and scaffold where appropriate. Tom Sherrington says “We are all aiming for the top of the mountain, but some of us will need more guidance, more time, more help.” We need to have the highest of expectations for all students no matter what their prior attainment, and accept that some will need slightly more scaffolding in order to get there. Now when I plan a lesson I start by thinking very carefully about my goal. My goal is not just to the top of the class, it’s about more than that. It’s about taking all learners to the next level of learning and scaffolding to support learners get there, creating the conditions to enable all to achieve success. Some students might need more explicit vocabulary teaching and some might need the work chunked up more explicitly. Some students might need more explicit success criteria and some might need a I do, we do, you do approach to exam questions. Some might need to hear you live model your thinking as you answer an exam question and some might just need more time. But in my classroom, the expectations are high, we will all do the same work, have the same learning challenges and my job is to provide the conditions to enable them all to be successful. Over time, just as the stabilisers come off the bike, I remove the scaffolding. The scaffolding is temporary, not permanent. In the latest Boys Don’t Try podcast Matt Pinkett, Mark Roberts and James Trapp all talk about occasions where students have suceeded remarkably because the expectations were ridiculously high. James talks about a top set class he had where he said to them at the start of the year that they were so good he was going to teach them the A-level curriculum instead. Because the expectations were so high and the motivation was there, the pupils produced increduble results. Mark talks about teaching his bottom and top sets exactly the same content with just more scaffolding for the bottom set and again students in the bottom set outperforming the top set. If the conditions are right, pupils will rise to the challenge.

So going back to differentiated learning objectives – what’s the answer? Well I still think it’s absolutely useful for students to know the big picture of the lesson. How does this lesson fit into our overall big enquiry question? What is the aim for the end of the lesson? Why are we learning what we are learning today? Again Matt’s blog has some brilliant advice:

“Yes, it helps students if they know why they’re learning iambic pentameter. Or the causes of the Wall Street Crash. Or quotations from Genesis. But, rather than wasting time with Learning Objectives, just tell ’em.

“We’re learning about X today because it’s going to help you with Y next week and one day you’ll be able/need to use it for Z.”

So this is what we do. Every lesson has a learning goal. It’s not copied down (what an absolute waste of time) it’s just communicated to the students in a straightforward way and then it’s straight into the learning. So if you are still using differentiated learning objectives or using “challenge” as a bolt on please think about lifting the lid off for your students. All students can get to the top of the mountain if we support and motivate them to get there. As Mary Myatt says “We like doing things that are difficult, as long as the conditions are characterised by high challenge and low threat.”

Rachel

For more on this I really recommend episode 5 of the Boys Don’t Try podcast and chapter 5 of the Boys Don’t Try book.

This video by Mary Myatt on differentiation and scaffolding is also superb.

Thank you for this. I left a school recently that insisted on differentiated outcomes. It made no sense to me. To battle it I used the outcomes to determine different sections of the lesson, for example, describe would be at the start and analyse further in. Now, in my new school, we have no such thing. We have an objective, of course we do. We have outcomes too. Pupils know why they are doing them, as per your example “We’re learning about X today because it’s going to help you with Y next week and one day you’ll be able/need to use it for Z.” We frame as many of our lessons as we can around a small enquiry question that feeds into the bigger question. We use scholarship throughout and at KS4 we then conclude our enquiry with a scholarship overview (something I am looking to cascade into KS3). Is this the right way, I’m not sure yet. We will see what happens when we can get into the classroom and deliver it. Still, the more voices against the prescribed differentiated outcomes, and even worse, writing them down, the better.

LikeLike

Thanks so much Cat. I totally agree and it sounds like you handled it as well as you could at the time in very difficult circumstances! Your curriculum sounds great. Thanks for taking the time to give such positive feedback, it’s really appreciated.

LikeLike

Having read “Boys don’t Try?” and this blog, I couldn’t agree more on challenging all students to reach the highest goals. Yet, when you teach 30 students who are mixed ability to reach that top goal, some will still reach that goal before others. Surely that is when the “challenge” as you mention above comes in. You focus on getting all students to reach that high goal; you have key students you need to make sure reach that goal so you work more with them, but some will have finished and will need challenging further – is that not where this challenge comes in?

LikeLike

I think if students exceed your expectations then absolutely you might then add in some additional challenge, but I think there’s a difference between that and planning for challenge as a bolt on if you see what I mean? I plan for the highest expectations for all as a starting point. Hope that makes sense.

LikeLike

This is a great read and has always been the way I’ve approached teaching. Accept nothing less than excellence but ensure the scaffolding is there, “A rising tide lifts all boats”.

LikeLike

Thanks so much! Totally agree

LikeLike